This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure for more information.

In part one of my Mr. Wow callout post, I made the unremarkable observation that our healthcare system is a mess and needs a serious overhaul. I also made the case that the two prominent camps vying to orchestrate that serious overhaul—the more government or statist camp and the less government or freedomist camp—both have legitimate fears regarding the involvement of government in healthcare, or the lack thereof, and both sets of fears need to be addressed if we want to do healthcare reform right.

This post proposes a number of reforms that will hopefully assuage the fears of both camps and make our healthcare system decidedly better. Here we go.

Crafting a Healthcare System that Addresses both Sets of Fears

The statist camp quite reasonably fears the freedom of healthcare providers to charge whatever they want for their services. Such freedom very often equates to the patient or the insured being legally extorted. “Accept our unconscionably high medical bills, drug prices, or insurance premiums or go without lifesaving care. It’s your choice.” The statist camp also quite reasonably fears the ability of America’s charitable heart, while formidable, to completely bridge the gap between needs and means on the healthcare front. Healthcare prices are too dear, and there are just too many broke and unhealthy Americans. Without a robust healthcare safety net imposed by the state, then, a lot of broke Americans stricken with dire but fixable diseases or injuries would have little recourse but to suffer and die.

The freedomist camp quite reasonably fears our government’s stewardship of our tax dollars and our freedoms. Our government has proven itself wholly unable to resist the ignoble demands of those with the deepest pockets or the shrillest tongues. The end result of this weakness is government programs that are inefficient, costly, and stultified, and far better at fostering incompetence and dependency amongst the governed than competence and self-reliance. A prime example of this is healthcare itself. For the past six decades, our government has been steadily increasing its control over healthcare. It now spends more on healthcare than ever (both on a per capita and inflation-adjusted basis), and it now regulates the healthcare industry more than ever. And what have we gotten for all this well-intentioned buttinskiness? Is healthcare affordable? Do surgeries, treatments, and drugs cost less here than they do in other developed countries? Are Americans better at managing their health than they were just a generation or two ago? The sad truth is that our government has failed miserably at controlling healthcare costs and engendering healthy lifestyles. And the freedomist camp quite reasonably fears that this impotence will only get worse should we go the full-blown socialism route. Our government will become even more beholden to Big Doctor, Big Hospital, Big Medical Equipment, Big Pharma, Big Bureaucracy, and Big Identity (i.e., racial, ethnic, and gender chauvinists), and those who value their freedom and paychecks will really get clobbered. Hello, healthcare oligarchy. Goodbye, paycheck freedom.

First-Principles Thinking

At first glance, crafting a healthcare system that addresses the legitimate fears of freedomists and statists alike seems impossible. How do you have limited government and paycheck freedom and ensure that every person in a country of 330 million people has all the healthcare that he or she requires? But what if, by some miracle, healthcare prices in America mirrored healthcare prices in Mexico? If that were the case, a lot of our healthcare problems would go away overnight. The typical American would be able to cashflow the minor medical stuff and easily afford healthcare insurance that covers the major medical stuff. Our government, in turn, would see its healthcare bills drastically cut, perhaps by half. Rather than spending $722 billion and $448 billion this year on Medicare and Medicaid respectively, our federal government would be spending closer to $361 billion and $224 billion respectively.

The first order of business for any worthwhile healthcare reform, then, is to not just get healthcare prices under control but to drastically lower them. And I don’t mean just lower them for the patient via “free” full-blown socialized healthcare. I mean lower them for whoever is paying—be it the patient, or be it a third-party charity, insurance company, or government agency.

The good news is that we know how to lower prices without producing dreadful queues and without stifling worthwhile innovation. It’s called the free market. Take price transparency and combine it with a competitive environment (i.e., an environment in which barriers to entry on the supplier front are trivial or non-existent, suppliers have to fight for customers, and customers can easily comparison shop to find the best deal) and you have the greatest tool ever devised to lower prices and spur innovation and abundance. A perfect example of this is computers. The first computer I bought, some 35 years ago, cost around $2,000, had 20 megabytes of storage, and required a sturdy table to support it. The last computer I bought, which was just over a year ago, cost around $200, had 64 gigabytes of storage (64,000 megabytes), and could comfortably fit in my pants pocket.

Okay, here’s how I devised my illustrious healthcare overhaul. I started with the following three goals:

- Create an environment for the supply and the consumption of healthcare that is so competitive, healthcare prices in America rival healthcare prices in Mexico, and the typical American can handle his or her healthcare costs by him or herself without relying on government aid or subsidies.

- Ensure that the government has sufficient tax dollars to operate a healthcare safety net that can address the healthcare needs of the needy (i.e., the poor, the medically unlucky, and the uninsurable).

- Ensure that no American will ever lose his or her paycheck freedom and be made a slave to whatever complex captures the heart of the political majority—be it the military-industrial complex, be it the education-industrial complex, or be it the healthcare-industrial complex.

Then, I asked myself what reforms would bring the above goals to fruition. My spectacularly fertile mind produced 18 such reforms. Here they are.

One: Expand Article One, Section Eight of the Constitution

It’s time to end the charade and amend the Constitution so Congress’s enumerated powers properly align with our desire for a safety net that addresses the healthcare and income needs of our most vulnerable brothers and sisters. Here’s my suggestion:

Amendment Twenty-Eight

In addition to the other powers enumerated in Article One, Section Eight of the Constitution, Congress shall also have the power to spend up to twenty-five percent of its annual budget on the provision of healthcare and up to twenty-five percent of its annual budget on the provision of income support.

At least seventy percent of the federal government’s healthcare spending shall be earmarked for those who have obtained an age of eighty percent of the US life expectancy or higher.

At least seventy percent of the federal government’s income support spending shall be earmarked for those who have obtained an age of eighty percent of the US life expectancy or higher.

The federal government shall recalculate what constitutes eighty percent of the US life expectancy every five years and this recalculation may only be recalculated upwards. If the US life expectancy should drop over a five-year period, the previous eighty percent calculation shall remain in effect.

The federal government may reduce the amount of healthcare and income support to wealthy citizens. Any reduction, however, shall not exceed fifty percent of the standard statutory benefit.

The federal government may become a producer of healthcare by operating hospitals and clinics, manufacturing drugs, and providing healthcare insurance. Whenever it becomes a producer, however, it must provide its counterparts in the private sector with the following tax options:

Option One: No corporate, property, or sales taxes, a minimum five percent dividend (for publicly-traded corporations only), and total compensation for the company’s top-paid executive capped at a multiple of the total compensation for the company’s lowest-paid employee. This multiple shall be determined by Congress and shall be no smaller than ten and no larger than twenty-five.

Option Two: Same tax obligations of any other business or corporation, no minimum dividend requirement, and unlimited compensation potential for the company’s top-paid executive.

Neither the federal government nor the several states may weaponize the provision of healthcare or income support by discriminating against or denying benefits to any American citizen because of his or her political views or beliefs, however unpopular or reprehensible.

Where I’m Going with This Proposed Amendment

- Fidelity to the Constitution. It makes programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security unambiguously constitutional. It also signals to future Americans that political shortcuts will no longer be tolerated. If you want Congress to do more, do the hard work and amend Article One, Section Eight of the Constitution.

- A robust safety net. The above amendment would allow Congress to spend up to 50 percent of its budget on healthcare and income support. For the current budget, such authority would allow Congress to spend $12,697 per Medicare recipient, $7,357 per Medicaid/CHIP recipient, and $17,246 per Social Security recipient. Hardly a miserly safety net.

- Get the governing to actually govern. If you’re a politician, it’s easy to govern with a printing press, a gargantuan credit line, and a Santa Claus mindset. Just promise your constituents more money and get the Treasury to print or borrow whatever it takes to fulfill that promise. But such “governing” is bad for constituents and the economy. It turns constituents into enfeebled losers who are much better at consuming than producing, and it eventually obliterates what every economy needs to thrive—economies thrive on work, thrift, and risk-taking, not sloth, welfare, and debt. This amendment will begin the process of turning our politicians into statesmen and stateswomen. They will finally have a cap on how much of a Santa Claus they can be, and they will eventually be forced to actually say “no” to their constituents’ ever-greater yelps for more free stuff.

Quick aside: The above percentage allotments pretty much line up with current practice. Medicare and Medicaid account for 24 percent of the current federal budget, and Social Security accounts for 23 percent of the current federal budget. Also, about 70 percent of Medicare and Medicaid spending goes to those aged 65 and older, and 70 percent of Social Security spending goes to those aged 62 and older.

Another quick aside: This post is about healthcare reform, of course, but I to decided to add the income support (i.e., Social Security) component to this proposed amendment as well. It makes little sense to formally place the healthcare component of our desired safety net into the Constitution and ignore the income support component—especially when not ignoring it only costs a couple of extra sentences.

Two: Amend the Constitution to Limit the Government’s Power to Tax

Spending is voting in an economic sense. You vote every day when you decide what people, businesses, and institutions are worthy of your money and what people, businesses, and institutions aren’t. Not placing limits on the government’s power to tax is thus an invitation to voter suppression, and voter suppression in an economic sense is every bit as noxious as voter suppression in a civic sense. Here’s an amendment that will ensure whoever earns an income gets to decide how the overwhelming bulk of that income is spent.

Amendment Twenty-Nine

Congress and the several states will have the power to tax individuals as follows:

Federal Taxation

The standard deduction for each individual taxpayer shall be at least ten percent of the previous year’s median household income.

The standard deduction for a married couple filing jointly shall be at least twenty percent of the previous year’s median household income.

On income up to the 90th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution, the combined tax from all forms of federal taxation save tariffs shall not exceed fifteen percent.

On income from the 90th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution up to the 99th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution, the combined tax from all forms of federal taxation save tariffs shall not exceed twenty percent.

On income from the 99th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution and above, the combined tax from all forms of federal taxation save tariffs shall not exceed twenty-five percent.

State Taxation

The standard deduction for each individual taxpayer shall be at least five percent of the previous year’s median household income.

The standard deduction for a married couple filing jointly shall be at least ten percent of the previous year’s median household income.

On income up to the 90th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution, the combined tax from all forms of state taxation shall not exceed ten percent.

On income from the 90th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution up to the 99th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution, the combined tax from all forms of state taxation shall not exceed fifteen percent.

On income from the 99th percentile of the previous year’s household income distribution and above, the combined tax from all forms of state taxation shall not exceed twenty percent.

General

Neither Congress nor the several states shall grant preferential tax treatment to income derived from capital gains. Capital gains, however, must be indexed for inflation so only real gains are taxed.

Neither Congress nor the several states may impose any type of payroll tax.

Save for the business tax options outlined in Amendment Twenty-Eight, neither Congress nor the several states may provide any type of tax preference or loophole to any specific taxpayer, business, or group.

Ten years after the adoption of this amendment, neither Congress nor the several states may borrow money to pay for anything other than capital goods that have a useful life of more than one year.

Ten years after the adoption of this amendment, neither Congress nor the several states shall guarantee the recipient of any entitlement program a set amount of money. Congress and the several states shall only guarantee the recipient of an entitlement program a set share of the entitlement program’s revenues.

Where I’m Going with This Amendment

- Paycheck freedom defined. You control a person’s paycheck, you control a person’s values. You decide for him or her what his or her spending priorities should be. And once you control a person’s values, you effectively control his or her mind. What he or she thinks is rendered utterly moot. He or she has no choice but to be a cog for the government and the political majority. A maximum 25 percent tax for all government combined stops paycheck slavery in its tracks. I, of course, think the maximum tax should be less. If a tenth of one’s income is good enough for God, it should be good enough for the government. But for reasons that are too lengthy to discuss now, small government functioning on small revenues is no longer an option, and the 25 percent maximum tax strikes me as a reasonable balance. The government and the political majority get its cut to do glorious things, and the typical American retains enough control over his or her paycheck to ensure that his or her values and mind still matter.

- Why less paycheck freedom for the 9 percent and 1 percent. I’d rather see the 9 percent and 1 percent have the same paycheck freedom as the 90 percent (25 percent maximum tax for all government combined). They are far better stewards of money than our government will ever be. But politically it isn’t feasible. The average American has been conditioned to believe that he or she is entitled to partially live off the wealthy. Moreover, our country is so much in debt, and so many of our fellow Americans are dependent on government handouts, granting the same paycheck freedom to the 9 percent and 1 percent would crater government revenues and spark a revolution. A 35 percent maximum for the 9 percent and a 45 percent maximum for the 1 percent are reasonable compromises.

- Goodbye preferential treatment of capital gains. On the one hand, I understand why capital gains have been granted preferential tax treatment. We want to encourage Americans to take risks and invest in the future, and we want to account for the detrimental effects of inflation. The big problem with this line of thinking is that Americans don’t need artificial encouragement to take risks and invest in the future. The larger returns that the stock market has delivered historically are all the encouragement Americans need to take risks and invest in stocks. Inflation is an issue, however. So the obvious solution is to treat capital gains like regular income and index them to inflation. You hold a mutual fund for ten years and have a $50,000 capital gain after selling it. But over that ten-year period, the cumulative amount of inflation comes in at 16 percent. So rather than paying regular income taxes on $50,000, you pay regular income taxes on $42,000. The remaining $8,000 isn’t taxed.

- Goodbye payroll taxes. For the current fiscal year, the federal government will collect $1.932 trillion from income taxes and $1.373 trillion from payroll taxes. Combined, income and payroll taxes will bring in $3.305 trillion. Three point three-zero-five trillion, in turn, is 15 percent of our national income. This amendment will thus bring in all the money the federal government needs to carry out its enumerated powers, including the safety net powers formalized in Amendment 28. (Higher tax rates for the 9 percent and the 1 percent will offset the cost of the standard deduction.) And for an added bonus, getting rid of payroll taxes will sever the connection between gainful employment and Social Security and Medicare. Eligibility for these entitlements will be largely based on reaching a certain age. The federal government will thus have an easier time means-testing these programs and reducing benefits to the wealthy.

- Goodbye unequal protection of our tax laws. Why is the government allowed to grant a tax loophole to one and but deny it to another? For example, I don’t agree with AOC on much, but I totally agree with her stance on the Amazon kerfuffle. Why should Amazon get a tax credit for creating jobs and not every other business in New York that creates jobs? If providing tax credits for job creation makes sense, it should apply to all. This amendment will make equal protection of our tax laws the law of the land and stop the nonsense of states and municipalities competing against each other to see who can do corporate welfare best.

- Getting the governing to actually govern, part two. Again, it’s easy to govern with a printing press, a gargantuan credit line, and a Santa Claus mindset. This amendment will finish what Amendment 28 started and finally turn our politicians into statesmen and stateswomen. Borrowing money for entitlements, pensions, and other operating expenses will no longer be allowed. Our politicians will only be allowed to borrow for capital goods (i.e., roads, dams, airports, ICBMs, etc.). This amendment will also crush the ability of our politicians to bribe the voters with ever bigger entitlement payouts. Future entitlement recipients will no longer be entitled to a set payout or benefit. They will only be entitled to a set share of an entitlement’s revenue, and such revenue will have a hard ceiling because of the constraints this amendment imposes on the taxing power of the government.* Our politicians will have no choice but to focus their immense critical-thinking skills on how to make the economy more vibrant, how to make honest labor more appealing, and how to make the typical American more self-reliant.

* Quick aside. Here’s an example of how a set share would work. Suppose for the moment that Social Security revenue is equal to $1.2 trillion and 70 percent of this revenue is earmarked for old-age insurance. Seventy percent of $1.2 trillion is $840 billion. Now let’s further suppose that there are 49 million old-age insurance beneficiaries. Each beneficiary would be entitled to 1/49,000,000 of the $840 billion. That set share payout would equal $17,143 annually or $1,429 monthly. If Social Security revenues increased and the number of old-age insurance beneficiaries remained the same or decreased, the set share payout would increase. Conversely, if Social Security revenues decreased or remained the same and the number of old-age insurance beneficiaries increased, the set share payout would decrease.

Three: Mandate that Providers Must Advertise their Prices and Abide by Them

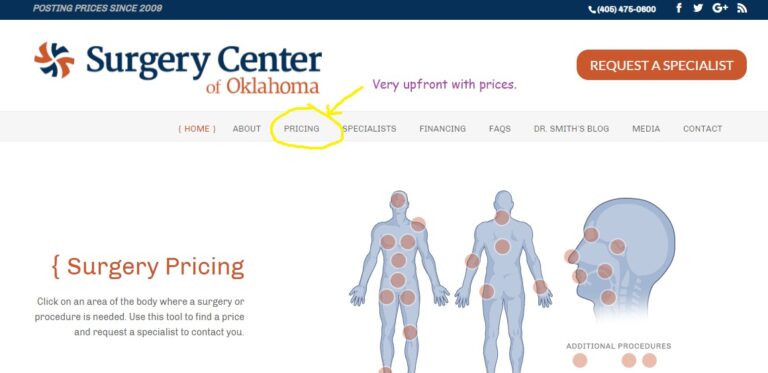

Check out the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, a hospital in Oklahoma City that is very upfront about its prices. Need a hip replacement? That will run you $15,499. Hernia repair (inguinal)? That currently goes for $3,060. How about rotator cuff repair? Six thousand, one hundred and forty-nine dollars.

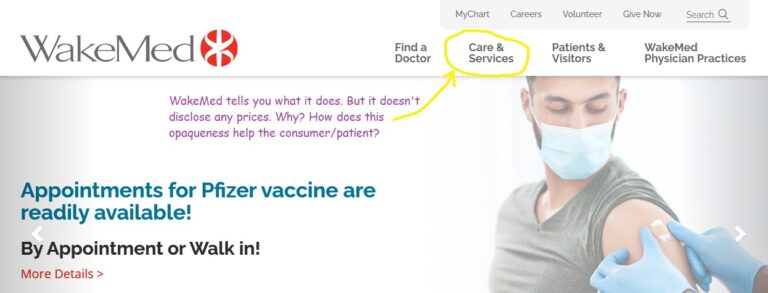

Now try to do this with a hospital near you? I tried this with WakeMed, one of the major hospital systems in my area, and it was impossible to find prices. Here are the homepages of the Surgery Center of Oklahoma and WakeMed.

Congress needs to mandate that every healthcare provider must be upfront with its prices. If a healthcare provider has a webpage, it must have an easily findable link to its pricing menu on its homepage. And it should also have paper pricing menus on hand in its lobby or waiting room. And Congress should also make sure that healthcare providers abide by their advertised prices. Advertised prices should include the cost of all customary inputs. In other words, healthcare providers shouldn’t be allowed to play games. “Our hip replacement only costs $12,000. But if you want anesthesia for the surgery, that’ll be an extra $5,000. And if you want good lighting in the operating room, that’s another upgrade. Our optimal lighting package is going for $1,000 right now.”

Before Mrs. Groovy and I went to Australia in 2019, we downloaded Google Maps for the states of New South Wales and Victoria to our phones. Think about that. In a matter of minutes, and for zero dollars, we had all the mapping data we needed to expertly navigate a road system on the other side of the planet. But if we wanted to know what healthcare providers within a 50-mile radius of our home were charging for an MRI or a root canal, we’d be out of luck. That’s ridiculous. And the only reason there’s no Google Maps of healthcare pricing is that our healthcare providers aren’t legally obligated to be upfront with their prices.

Four: Forbid Providers from Engaging in Price Discrimination

Here’s the game hospitals play. Surgery x costs x dollars. But depending on your insurance circumstances, you get a certain discount. If you have Medicare, your discount is 80 percent. If you have Blue Cross Blue Shield, your discount is 50 percent. And if you’re an uninsured, cash-paying patient, your discount is zero percent.

Why is this kind of discrimination tolerated? The only patients who should be getting any kind of discount are upfront, cash-paying patients. After all, upfront, cash-paying patients are paying for their care in full the day the care is delivered. Providers don’t have to deal with the hassle of submitting claims or arranging payment plans and then being reimbursed months later, if at all. So it would behoove providers to reward upfront, cash-paying patients with, say, a three or five percent discount. But whether or not a small amount of discrimination based on payment methods makes sense and should be allowed, discrimination based on insurance circumstances, regardless of the amount, doesn’t make any sense and should never be allowed. What a patient is charged for care should be based on the costs of the inputs involved. And those inputs, providing we’re talking about the same surgery or treatment being provided by the same provider, are the same for the Medicare patient, the Blue Cross Blue Shield patient, and the uninsured patient.

Five: Reward Patients for Being Frugal

Healthcare is the only thing we consume by suspending rational consumer behavior. Could you imagine walking into a car dealership and not encountering a single price? You just pick the car and options you want and sign the sales agreement and then a month later you find out what your car cost and what your monthly payments are.

Who in his or her right mind would buy a car like this? But this is how we buy healthcare. Apparently asking a doctor what his or her suggested care will cost is very rude—it’s as if you’re questioning his or her integrity and calling him or her a jackal. So we neither ask what things costs nor deign to shop around for the best deal, and we’re completely mystified why healthcare prices are forever spiraling upwards.

We got to bring rational consumer behavior to the healthcare market where feasible.* We got to make the consumer/patient more price curious and more price sensitive.

Reforms three and four would go a long way toward making the frugal consumption of healthcare a reality. Americans without healthcare insurance or with high-deductible policies are naturally price-curious and price-sensitive. Reforms three and four would give them the tools to act on these predispositions.

But what about Americans with low-deductible insurance? And what about Americans covered by Medicare or Medicaid? How do we get these Americans to be price-curious and price-sensitive? Here’s a suggestion.

Rather than insurance companies negotiating reimbursement amounts with every hospital and doctor in a given area, how about insurance companies providing a set reimbursement amount for surgeries and treatments and then letting its insured do the negotiating? The set reimbursement amount could be pegged to the median price of a surgery or treatment in a given area. Then the following incentives would apply: The cost of the surgery or treatment above the set reimbursement amount would be the complete responsibility of the patient. But the patient would split the savings 50-50 with the insurance company if the cost of the surgery or treatment were below the set reimbursement amount.

| Provider | Cost of Arthroscopic Knee Surgery | Set Reimbursement Amount | Difference | Patient Responsibility or Reward |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital A | $4,500 | $4,000 | $500 | Owes Hospital A $500. |

| Hospital B | $3,500 | $4,000 | -$500 | Gets a $250 bonus from his or her insurance company. |

This would be a great way to make the consumer/patient more price curious and price sensitive. It would also be a great way to eliminate the out-of-network crap in the private insurance market and make Medicare and Medicaid recipients more attractive to hospitals and doctors. But how do you force insurance companies to adopt this business model, or at least offer it as an option to their customers?

As far as I can tell, Medicare and Medicaid pretty much follow a set-reimbursement-amount (SRA) business model. But their set reimbursement amounts are well below median prices and they neither punish Medicare and Medicaid recipients for being profligate consumers of healthcare nor reward Medicare and Medicaid recipients for being frugal consumers of healthcare. To get Medicare and Medicaid to fully embrace the SRA business model, however, would just require an act of Congress. Congress is ultimately in charge of CMS, so it can foist whatever rules and policies it wants on Medicare and Medicaid.**

Private insurance companies are another matter, however. Congress doesn’t have the authority to tell them how to run their businesses. But Congress can provide a carrot. Suppose for the moment that Amendment Twenty-Eight was adopted and Congress capped total compensation under the total compensation clause at 10x. Congress could then up this cap to 15x for any private insurance company that embraced the SRA business model. And if Amendment Twenty-Eight weren’t the law of the land, Congress could simply replicate its tax options by amending the tax code. How many private insurance companies would embrace the SRA business model and forego outrageous CEO pay in order to dramatically reduce their tax obligations? I can’t say for sure, but my guess is that most would. Finding a competent CEO who’s willing to suffer the indignity of “only” being paid, say, $600,000 annually shouldn’t be a bridge too far.

* Quick aside: It’s hard to be a rational consumer of healthcare when you’re unconscious and need emergency care. But in most healthcare situations, patients have time for due diligence and making sure they’re not getting ripped off.

** Another quick aside: Medicaid recipients certainly wouldn’t be expected to pay the overage of a set reimbursement amount. And nor would most Medicare recipients. But Medicaid and Medicare recipients should be eligible for a cut of the underage. There are some 96 million adults enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare. Incentivizing them to be price-curious and price-sensitive would save the taxpayers a lot of money.

Six: Allow Americans to Buy Equivalent Medications from a Foreign Supplier If They Can Save 50 Percent or More

According to The Washington Post, the NovoLog insulin pen costs $13 in Mexico. In America, the NovoLog insulin pen costs around $110. Any American who uses the NovoLog insulin pen could easily cut his or her insulin expenses in half by having his or her insulin prescription fulfilled by a Mexican pharmacy.

I’m all for a vibrant domestic pharmaceutical industry. The Covid 19 pandemic has painfully illustrated just how dangerous it is to be dependent on foreign suppliers of any critical medical device or product. But I also don’t want Americans humbled by a prescription drug that doesn’t humble poorer people in poorer countries. Allowing Americans to get their medications from foreign suppliers would be an effective check on domestic suppliers.

Congress could inject some much-needed competition into the prescription drug market by doing the following:

- Allow Americans to buy equivalent medications from a foreign supplier if they can save 50 percent or more.

- Wave the tariff for any medication imported under the 50-percent-savings rule.

- Mandate that the Department of Health and Human Services maintains a website that shows what foreign pharmacies/suppliers can save Americans 50 percent or more on their prescription drugs.

Seven: Promote Medical Tourism

Medical tourism is commonly defined as when someone travels abroad to save money on medical treatment. Surgery x costs $20,000 in America but only $5,000 in Costa Rica, for example. But what if we broadened this definition to include the crossing of state borders? A surgery that costs $20,000 in New York City may only cost $5,000 in Wheeling, West Virginia. And what if we encouraged insurance companies to embrace a borderless SRA business model? Americans could get a nice bonus and save insurance companies a lot of money by traveling to another state or country for their healthcare.

Again, the key to instituting this reform is getting insurance companies to embrace the borderless SRA business model. And again, Congress has the power to foist the borderless SRA business model on Medicare and Medicaid and incentivize private insurance companies to adopt it with very attractive tax and CEO compensation options (à la the options in my proposed Amendment Twenty-Eight).

Another way to help this reform along is to get the Department of Health and Human Services in the business of certifying healthcare providers in other countries. Patients and insurance companies would thus have an easier time identifying safe, competent, and SRA-suitable hospitals, dental practices, and nursing homes.

Eight: Allow Medicare and Medicaid Reimbursement for Foreign Delivered Healthcare

There is affordable, competent healthcare just over the border in Mexico. Millions of Americans are already taking advantage of this. But they’re doing it with their own dollars. They’re not doing it with Medicare or Medicaid dollars. This is crazy. There are obviously millions of Medicare and Medicaid recipients in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and Medicare and Medicaid could save a ton of taxpayer dollars by encouraging medical tourism.

And here’s another thing to consider. Roughly 30 percent of Medicaid expenditures are on long-term care for the elderly (see page 26 of the linked report). And from what I can gather, Medicaid pays 100 percent of the costs a nursing home incurs for administering care to a Medicaid recipient. There are no discounts. This means the cost savings of Medicaid encouraging medical tourism are huge. A nursing home in New York costs roughly $11,000 per month (see the average daily cost chart in the linked report). The cost of an equivalent nursing home in Mexico, Costa Rica, or Thailand would easily cost a quarter of that. And the notion that Americans would consider a nursing home in a foreign country isn’t as farfetched as you might suppose. First, the bonus from the borderless SRA business model would be substantial and would easily cover the food and housing expenses of a family member who was willing to relocate and monitor the care being delivered by the nursing home. Second, we’re a nation of immigrants. Many elderly still have family in the old country, and the idea of spending their last remaining years in their country of origin would surely have some appeal.

Nine: Reward Americans for Being Healthy

The best healthcare is no healthcare. I’ve had remarkably good health over the past three decades and haven’t required any medical interventions beyond routine maintenance (i.e., annual wellness exams and a colonoscopy). Part of my sterling health record is the result of luck, of course. But part of it also has to do with mindfulness. I walk three miles every day, do resistance training six days a week, and keep my intake of sugary drinks, bread, and processed food to a minimum. The end result is that I’m one of those rare American adults who isn’t overweight. Another reason for my sterling health record is that I don’t engage in any risky behaviors. I don’t fraternize with the Bloods or the Crips, I don’t smoke, get blotto, or ingest illicit drugs, and I don’t need the rush of adrenaline to feel alive. A wild time for me is going to Dairy Queen for a Blizzard on a Saturday night—it isn’t hang gliding, bear-knuckle boxing, or running with the bulls.

Now imagine if I were the typical American adult. How many fewer hypertension or diabetes prescriptions would be written annually in this country? How many fewer knee or hip replacements would be performed? How many fewer broken bones would be set? How many fewer drug rehab stints would be required? And how many fewer gunshot and knife wounds would be mended?

The sad truth is that we pay a lot for healthcare because we require a lot of healthcare. We have too many sickly and mangled Americans chasing too few doctors. But what if this were reversed? If Americans were more mindful of their health—if they ate better, exercised more, and eschewed drugs, alcohol, tobacco, promiscuity, crime, and jackassery—we wouldn’t need nearly as much healthcare as we do now. There would be too many doctors chasing too few sickly and mangled Americans and this very welcome market imbalance would naturally bring down the cost of healthcare—both in a macro and micro sense.

To show what I mean, here’s a sample reward system:

| Health Metric | Reward |

|---|---|

| Normal weight. A person is not overweight or obese and remains that way for the year. | $500 |

| Significant weight loss. An overweight or obese person loses ten percent of his or her begin-year weight over the course of the year. | $500 |

| Minimum utilization. During the year, a person requires no healthcare beyond routine maintenance (i.e., wellness exam, breast exam, colonoscopy, etc.). | $250 |

The above metrics are just some basic health measures that popped into my head. Are they key to improving health and reducing the need for healthcare? Maybe. Maybe not. Deducing the best metrics and accurately measuring them, however, isn’t our biggest problem. Our biggest problem is paying for whatever reward system we devise. Here are two suggestions:

- Five percent rule. Providing the bulk of my reforms are adopted, especially reforms three and four, the cost of healthcare in this country would drop dramatically. The federal government would then be free to use its healthcare spending to promote healthy living and reduce the need for healthcare. This year, for instance, the federal government will spend $1.2 trillion on Medicare and Medicaid. Just five percent of that is $60 billion. That $60 billion, in turn, equates to 120 million $500 rewards. Since there are roughly 143 million overweight and obese adults in America, we could effectively launch a war on obesity tomorrow.

- Targeted rebates. A few months ago, Mrs. Groovy and I each received a $400 gift card from our healthcare insurer. Apparently, Blue Cross Blue Shield had a great year claims-wise last year and its customers were entitled to a rebate. But what if such rebates weren’t dispersed evenly amongst the insured? What if rebates only went to those who generated no claims beyond routine wellness exams (i.e., the physically fit and the medically prudent)? That would certainly light the proverbial fire under the proverbial asses of the physically unfit and the medically imprudent.

Ten: Make Medical Training Part of the Defense Budget

I am so sick of citizens from other developed countries lauding over us how morally superior they are because they have full-blown socialized healthcare and we don’t. Well, it’s easy to be morally superior on the healthcare front when you don’t shoulder the bulk of your national defense.

This nonsense has to stop. We’re broke and we’re getting lip from ingrates in Europe and the Far East. Let Europe worry about the Russians, and let Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand worry about the Chinese. It’s time to pull back on the empire and do something for the beleaguered taxpayer and patient over here.

Excellent, affordable healthcare is a national security interest, and one sure-fire way of achieving it is making sure that our healthcare professionals are graduated without debt. Make medical training part of the defense budget. Start reducing our commitments to NATO, SEATO, and whatever other TOs are out there, and use the savings to pay for the college expenses of aspiring doctors, dentists, nurses, and other medical professionals.

“Free” college for aspiring medical professionals shouldn’t come without strings, of course. Here are some crucial strings that need to be instituted:

No college will be eligible for DOD medical-training money if…

- It doesn’t have the same admission standards for every student it admits. (The DOD will not reward schools that penalize applicants for having the “wrong” skin color, ethnicity, or gender.)

- Its president’s total compensation is more than the POTUS’s salary.

- It doesn’t peg a professor’s total compensation to the number of courses he or she teaches each semester.

- The total compensation a professor receives for teaching any course exceeds 6 percent of the POTUS’s salary. (Six percent of the current POTUS salary is $24,000. The total compensation for a professor teaching six courses over the academic year would thus be $144,000 or less. If said professor taught ten courses over the academic year, his or her total compensation would be $240,000 or less.)

- It has a D1 athletic program in any NCAA sport.

- Any student expense (i.e., tuition, fees, books, room and board, etc.) rises faster than the rate of inflation.

- Any of its medical programs contain courses that have nothing to do with medicine. The DOD isn’t paying for a 40-course nursing degree when a 20- to 25-course nursing degree is more than adequate. And the same goes for doctors, dentists, pharmacists, etc.

Eleven: Make Malpractice Insurance Part of the Defense Budget

Again, a great way to make healthcare affordable is to reduce the overhead of doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. The average annual malpractice insurance premium for a doctor in America is $7,500. Since there are roughly 985,000 doctors in America, doctors spend a total of $7.4 billion annually on malpractice insurance. That’s a lot of money, of course. But it’s a pittance compared to the amount of money we contribute to NATO and SEATO. Covering malpractice insurance via the Defense Department is a win, win, win. Taxpayers are no worse off, doctors have less overhead, and patients see the savings from that reduced overhead in the form of lower bills.

Twelve: Mandate that Every Healthcare Professional Provide at Least Eight Hours of Free Labor Per Month

If our future healthcare professionals are going to get a “free” college education, they should be required to give a little back. Providing eight hours of free labor per month at some free clinic or urgent care facility seems more than reasonable.

Thirteen: Amend Licensing Laws so Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Can Do More Doctoring

Imagine if only math PhDs could teach math in our K-12 schools. That would not doubt elevate the quality—and cost—of our math teachers. But would it be wise? Do we really want math PhDs teaching second-graders how to add and subtract? After all, a bright high-school kid could effectively teach second-graders how to add and subtract. Wouldn’t it make more sense to have math PhDs teaching rarefied math (vector calculus, combinatorics, discrete mathematics, graph theory, etc.) and leave the teaching of mundane math to less credentialed but perfectly capable math teachers?

Well, this same analysis applies to healthcare. Having doctors do mundane things such as treating the common cold or removing ear wax is an extreme waste of talent and resources and needlessly drives up costs. Congress and the states need to amend licensing laws so nurse practitioners and physician assistants provide the bulk of everyday healthcare in this country. Let doctors do the rarified stuff—the brain surgeries, the heart surgeries, the hip replacements, etc.—and let nurse practitioners and physician assistants do the mundane stuff. The quality of healthcare wouldn’t suffer but the cost of healthcare would drop significantly.

Fourteen: Mandate that Doctors Must Adhere to a Fiduciary Responsibility

If generic drug A does the job, then doctors shouldn’t prescribe brand-name drug B because the manufacturer of brand-name drug B provides them with a kickback. Doctors shouldn’t just be concerned with a patient’s physical well-being. Doctors should also be concerned with his or her financial well-being. Requiring doctors to do what’s best in their patients’ financial interests would help reduce the amount of superfluous medicine that takes place in our current system.

Fifteen: Institute a Public Option

Statists firmly believe that the government can do things cheaper than the private sector because the price of a government-produced good or service isn’t inflated to produce a profit. Freedomists, on the other hand, believe the cost of politics (i.e., honest graft) does more to inflate the price of a good or service than the cost of profits ever could.

The good news is that we don’t have to argue or debate to prove which camp is right. We can have an actual test. And we can do this by providing a public option—by allowing any American adult under the age of 65 to solicit Medicare for healthcare insurance. But in order to have a proper test, though, we have to establish some ground rules so the government and private sector are competing on a level playing field. Here are four must-have ground rules:

- No subsidies for Medicare buy-ins. The cost of a Medicare premium must reflect the total cost of insuring the non-elderly person buying into Medicare. Medicare can’t use taxes or borrowed money to lower the premiums for any non-elderly buy-in.

- No taxes for private insurers. Medicare doesn’t pay corporate, property, and sales taxes and neither should any private insurance company competing against Medicare.

- Capped CEO compensation. The CEO of Medicare doesn’t get paid millions of dollars a year and neither should the CEO of a private insurance company competing against Medicare—especially when the company he or she is running isn’t obligated to pay corporate, property, and sales taxes. The 10 to 25 multiple I proposed in Amendment 28 strikes me as eminently fair. If the total compensation for a particular insurance company’s lowest-paid employee were $30,000, the CEO of this insurance company would have a total compensation package worth between $300,000 and $750,000.

- Same enrollment constraints. If Medicare can’t refuse to insure a non-elderly buy-in with pre-existing conditions then neither can private insurance companies.

Sixteen: Medicare Part P

Let healthcare insurance be insurance. Insurance is purchased to protect one’s finances from unlikely events (i.e., your car getting totaled or your house burning down). It isn’t purchased to protect one’s finances from likely events (i.e., your car needing an oil change or your HVAC system needing fresh filters).

The problem with healthcare insurance being insurance is that many Americans have pre-existing conditions that make the future consumption of healthcare a certainty. Insurers naturally have to adjust to this reality by jacking up premiums for those with pre-existing conditions or by refusing to take on clients with pre-existing conditions in the first place.

To work around this problem, I suggest the following:

- Private insurers can’t deny coverage to anyone with a pre-existing condition. But they also have the right to base their premiums on risk. If a middle-aged person with diabetes is three times the risk of a middle-aged person without diabetes, then the annual premium for our middle-aged diabetic should be three times the annual premium of our middle-aged non-diabetic.

- Create Medicare Part P to assist those with pre-existing conditions. In other words, Medicare would cover all or part of the difference between a non-pre-existing premium and a pre-existing premium. If the annual premium for a middle-aged person without a pre-existing condition were $6,000 and the annual premium for a middle-aged person with a pre-existing condition were $18,000, Medicare would cover some portion of the $12,000 difference. If our middle-aged person with a pre-existing condition had a working-class income, Medicare would cover the entire difference. If he or she had an upper-middle-class income, Medicare would only cover, say, half of the difference.

Seventeen: Create and Maintain a Database of Unpaid Medical Bills to Promote Healthcare Charity

The older I get, the more leary I become of outsourcing my charity. I’d rather give directly to a needy individual than give to an organization that gives to needy individuals. You just don’t know how much of your charity will actually make it to the needy when you rely on an intermediary.

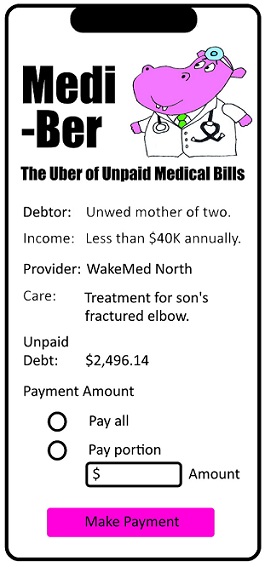

Now suppose for a moment that there was an Uber of unpaid medical bills—let’s call it Mediber. You can go to Mediber and see who in your community is struggling with medical debt. You can then use Mediber to choose a debtee and pay all or some of his or her debt. To show what I mean, here’s a screenshot of my hypothetical Mediber.

A Silicon Valley tech firm could no doubt produce a very compelling Mediber app and make a lot of money on transaction fees. But this app rightfully belongs to the feds and the states. The feds and the states have the tax and entitlement participation information to make sure only Americans of modest means are helped with their medical debt.

Eighteen: Establish Medi-Loans

Americans have no problem with a $500-per-month truck payment for seven years. But getting a loan for a life-saving surgery is beyond the pale. I’d love to see the federal government get out of the student loan business and get into the medical loan business. But for the federal government to do medi-loans right, it would have to abide by the following guidelines:

- No interest medi-loans would have to be paid back in a reasonable amount of time—ten years or less.

- The person receiving the medi-loan would need to have a job.

- Payments for medi-loans would be deducted from the loanee’s paycheck just like income taxes are.

- The federal government couldn’t use borrowed money to issue medi-loans. Medi-loans would have to come from tax dollars collected from income, sales, and corporate taxes and earmarked for healthcare (i.e., it must be included in the 25-percent budget constraint outlined in my Amendment Twenty-Eight).

Final Thoughts

I have two points to make before I wrap this up.

First, I’m just a little ol’ country blogger from North Carolina. I’ve never worked in healthcare and though I profess to have a spectacularly fertile brain, my brain is far more pedestrian than otherwise. But I think my reforms do a nice job of striking a reasonable balance between freedom and security and introducing some much-needed competition to our healthcare system. I can only imagine what reforms someone with a more informed and more fertile brain could bring to the table.*

Second, this post is purely academic. The above reforms have zero chance of ever becoming a reality so there’s no need for anyone to get butthurt or triggered. The statist mindset is strong in our withering republic and we will eventually have full-blown socialized healthcare just like every other developed country. And just like every other developed country, our full-blown socialized healthcare will be marred by ISIS—incompetence, sloth, inefficiency, and stagnation. But no worries. The sorry people will love their sorry healthcare because it’s “free” and because the propagandists in education, journalism, and entertainment will tell them to love it.

Okay, groovy freedomist, that’s all I got. What say you? Do my suggested reforms address the legitimate fears of both the freedomist and statist camps and make healthcare better? Or are my suggested reforms just a bunch of right-wing hooey? Let me know what you think when you get a chance. Peace.

* Final aside: The reformer with a more informed and more fertile brain would have to abide by the same constraints as I did. In other words, the reformer would have to do his or her damnedest to protect paycheck freedom and make sure the healthcare-industrial complex is kept at bay.

Capping anyone’s income to six figures is a bad idea. Your range of pay for CEO’s is around one tenth of current pay. The idea that you would limit executive pay to 10% of what a free market has equillibrated to is on the ludicrous side. It’s a totalitarian idea that doesn’t belong with the rest of your brainstorming and it is such a tiny amount of money it has zero impact on healthcare costs. I generally enjoy your concepts but you jumped the shark on CEO pay.

I don’t disagree. I also believe the number of CEOs with eye-popping compensation is small in number. I’m just trying to navigate a political environment that is very socialist. So I asked myself, “How do I make the elimination of corporate, property, and sales taxes for businesses palatable?” And the only thing I could think of was pegging CEO compensation to a multiple of the lowest-paid employee’s compensation. No cap surely makes sense and is surely synonymous with freedom. But would it fly? Damn! Nobody said solving our healthcare woes was going to be easy. Again, I don’t disagree and I think your “jump the shark” accusation is fair. Thanks for the pushback, my friend.

Oh, I just remembered. Don’t forget, my proposed CEO compensation cap is totally voluntary. Boards will only be constrained by it if they want to forego corporate, property, and sales taxes. They would still be free to pay their CEOs tens of millions of dollars each annually if they want. They just have to decide if uncapped CEO pay is worth the tax liabilities uncapped CEO pay would engender.